This helpfully drawn graph by David Weston on today’s blog post at the Teacher Development Trust has helped visualise a problem that has been growing in my mind for at least ten years. I referred to it obliquely in a previous post entitled “Moral Purpose” when I mentioned the notion of Game Theory in assessments. Game Theory is one of those things that I haven’t really understood until now, but a really helpful post from maths teacher Owen Elton this morning has helped me understand it better, and in particular how it applies to the particular situation in the English education system.

This helpfully drawn graph by David Weston on today’s blog post at the Teacher Development Trust has helped visualise a problem that has been growing in my mind for at least ten years. I referred to it obliquely in a previous post entitled “Moral Purpose” when I mentioned the notion of Game Theory in assessments. Game Theory is one of those things that I haven’t really understood until now, but a really helpful post from maths teacher Owen Elton this morning has helped me understand it better, and in particular how it applies to the particular situation in the English education system.

It started in a Year 6 class I had a decade or so ago. I’d been in the school in a deprived part of Birmingham for a couple of years and we had had a new headteacher that year. The head, who hadn’t shown much interest in my class for most of the year, took a sudden and very intense interest in the class during SATs week, including offering to help read the questions to the children in the maths SATs papers – as everyone knows, maths is not a test of reading and children who can’t read so well shouldn’t be disadvantaged in their maths just because odd their poor reading skills. So in that first test, I saw the headteacher position himself next to a girl who was very border line between level 3 and 4. He read the questions, yes, but then went on to talk her through the steps to solving the problem. He didn’t actually tell her the answer. Then in the next test, which was a mental mathematics test read by a lady on a cassette tape (a voice that all teachers in England will know very well), he stopped the tape. After the first 5 questions the children were allowed some ‘extra thinking time’ – and likewise after the next 10 questions.

I felt really uncomfortable about what had happened, so the next day, before schools started and before the final test of the week I went to the headteacher to express my discomfort. “Did we go to far?” he asked, smiling. I felt that we had and we agreed not to support the children so much. Relieved, I went away to prepare my children for the final test of their SATs week. And after it, I remember he called back into his office, I thought to ask me how I thought the week had gone. But no, he told me that he had seen me playing too roughly with the Year 6 boys at playtime during football. I should be careful not to do that he asserted. I knew what he was saying – don’t grass me up and I won’t grass you up.

It was a difficult time for me – I spent the next year or so really struggling with my practice and it was only when I moved schools that I started to regain my confidence.

But aside from that, it was my first experience of the grey area of over-support. The facts are:

- There are no entirely externally assessed national tests in England.

- Primary schools are held accountable by national government using the results of their tests.

- Teachers are held accountable by their schools using the outcomes from tests.

As Owen Elton says when analysing the ‘teacher’s dilemma’ in the blog post I referred to above, teachers “should mark generously”. He was referring to coursework, but translating that to SATs tests in primary schools, teachers should give whatever support they can to their children.

Now, I would maintain that stopping a mental mathematics test to give children more thinking time is cheating, but there are grey areas of support, which as David Weston says would be called cheating by some, but not by others. Here are some:

- test papers can be opened up to an hour before the test by their teachers – but should they be?

- children can be placed in different rooms and group sizes around the school to give them different levels of emotional support – but should they be?

- teachers can read test questions and instructions to their children – but should they do so?

- Children are allowed to sit in the same room where they have done their learning – but should they?

For each of those examples above I can think of examples where the regime has been abused. For example:

the deputy headteacher who opened the writing tests an hour earlier, saw that the test was on a certain form of writing and spent the next 45 minutes reminding children about features of that kind of writing…

Or

the school where a friend’s daughter was placed in a room with only two other students and found that the atmosphere was a lot more conversational than previous tests had been…

Or

my son reported his teacher had raised her eyebrows and pointed at an answer in a maths test…

Or

the headteacher who accidentally left the science display up in the classroom where the science test was being sat…

And of course, when a teacher has stepped into the grey area one year, is it easy to step back from it? Doesn’t the grey area get bigger?

My second clue that a grey area of over-support existed was in speaking to a colleague from a university a few years ago. She had noticed that the year that they had had to introduce plagiarism checkers as standard was the year that corresponded with the students who had sat the very first SATs back in 1996. She also noticed that it was that same year group of students who suddenly demanded far more from their tutors. It was like they had lost their independence and almost needed their studies doing for them.

My third clue was looking over the shoulder of my mother who is still a marker for one of the exam boards. She was marking a set of maths coursework, and each one was virtually identical. Some of the names and places and numbers were slightly different from each other, but the format and the nature of the maths represented was identical – no child seemed to demonstrate any independent thinking or mathematics. But I suppose is there any wonder that secondary school teachers need to over-support their students if their students are assessed in an over-supportive way at primary school?

The final pointer towards over-support has been the GCSE English fiasco that has been debated long and heard over the last few months. Who is the wrong? The schools? The exam boards? The politicians? I think we all have to take some of the blame. And hears why:

When I hear students say things like “the system has let me down”, which is a quote I’ve heard from the news in recent weeks, that’s when I have to think that actually we all share some of the blame. We have created an assessment culture that is at best over-supportive and at worst is cheating. Michael Merrick foretold this in his post back in March, when he asked the question: “When primary responsibility for success or failure is taken away from the student and placed instead on the shoulders of teachers, what effect might this have on the education system? ”

To me it is inevitable that we have come to this point – we are so lost in ‘playing the game’ or ‘keeping the Ofsted wolf from the door’ that we have forgotten that an education system should be built to let individual students triumph. Is ours? Is it really?

I don’t do a good job by moving my school to outstanding, or moving my school up the league table – I do a good job by moving my students from consumers to contributors, by educating them so they can achieve for themselves. Yes, hopefully those 2 things are synonymous. In an ideal world they would be. But in the real world (to quote Michael Merrick once more) “that murky landscape of educational ethics comes into view, with exhausted and anxious teachers straying over the once clear demarcation lines, in the process creating a culture that absolves students from real responsibility (and even, sometimes, effort) in their own learning and achievement.”

And to quote Frank Zappa, which is becoming a bit of a habit at the moment: “go to the library and educate yourself if you’ve got any guts.” And he said that in 1966.

This helpfully drawn graph by David Weston

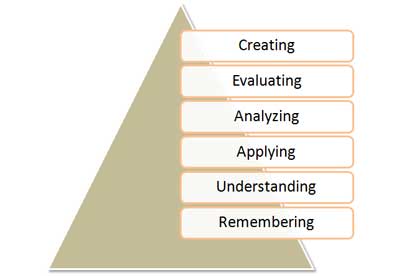

This helpfully drawn graph by David Weston  It seems we’re very keen in the teaching world at the moment to find ways of teaching those higher skills of evaluating and creating. But we miss the vital step between remembering things and applying them – that of understanding them.

It seems we’re very keen in the teaching world at the moment to find ways of teaching those higher skills of evaluating and creating. But we miss the vital step between remembering things and applying them – that of understanding them.