One of the criticisms that Ofsted had for us last June was that we had a lack of consistency.

So we revamped the marking policy and the presentation policy. We did a book scrutiny and a series of learning walks. We wrote up what we found and fed it back to staff as whole school feedback. Nothing changed.

Here’s something I’ve learned: whole school feedback does absolutely nothing. All it does is make the best teachers feel more guilty and therefore more stressed than they already are, and the teachers who need the most development don’t realise just how much development they need. So as a leader it may feel like you are giving the staff a consistent message, which surely must help increase consistency, but actually it’s doing just the opposite.

That wasn’t entirely a revelation for me, as it was the kind of thing I knew in principle, but living and breathing the reality of needing to make rapid changes in a few months really made me learn it.

Since then I have started an ongoing document for each staff teacher which encapsulates areas for development and actions to take around the teaching of mathematics. This has been great, because each teacher has their own needs – their own starting points – but each teacher also has two aims in terms of their quality of work: compliance and development.

Every school, every organisation, has their own set of non-negotiables to which their staff must comply. That is the first step to achieving consistency. Some people find this harder than others – my Achilles heel is my handwriting, which I can do well when I concentrate, but at the end of marking 90 books, if I’m not careful it does tend to drift towards the illegible. Achieving consistency is about giving the individual feedback to help each staff member become compliant with the non-negotiables. At my school, it’s not good telling all the staff to improve their handwriting in their marking,as that’s only a message that the select few need to hear.

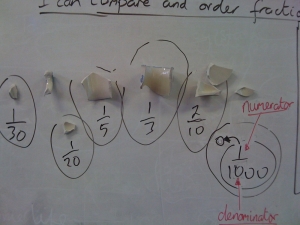

Development is even more important than compliance. We all want to be the very best teacher we can be. Three things make us good teachers: subject knowledge, pedagogy and motivation, but we’re all strong in different areas. It’s the job of our senior leaders to identify the areas that we need to get better at and give us just the right guidance to become even better in each of those areas. And again, if you were to only work on subject knowledge for all staff, when behaviour management (part of pedagogy) was the issue, you would not be achieving consistency.

It’s been my job to raise standards in maths teaching across the school. I’ve done this by working inconsistently on compliance and development with different teachers, giving them individual written guidance to do so. We’re not there yet, but by feeding back inconsistently, I hope that I have increased consistency.