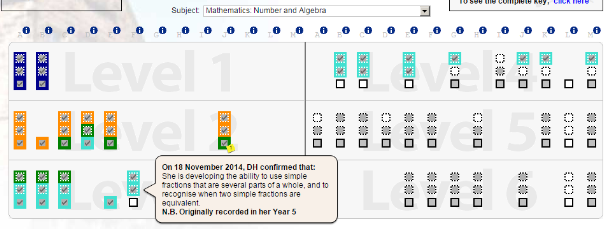

I’m a big fan of conditional formatting. Look how you can put a number in and the whole box changes colour! Amazing!

I had done a lot of conditional formatting by the time Ofsted arrived last June. But Ofsted don’t want colours. They just want the numbers. And by the time they arrived, whilst I controlled the colours, I had no idea what was going on with the numbers.

The core of the problem is that what I thought was the assessment system, was actually only the data capture system.

There are a whole load of things that need to happen before a number appears on a spreadsheet to indicate how well a child is doing. The child needs to be taught something. They need to then really learn that thing so they can apply it ways that aren’t in the routine lesson in which they were originally taught the thing: like a test, or a piece of extended writing. They need to evidence they have learned the thing too. Tests are fine, but remember that books are king, so the evidence has to be in the books. After that you can quantify how much the child has learned the thing. Then you can put that quantity into a spreadsheet. You can total it, average it, filter it and apply a whole load of other formulae to it.

And if you’re like me you’ll want to colour it.

That last part is the data capture system. But the whole paragraph is the school assessment system.

Somewhere in that system, you will have defined the criteria ‘good’ and ‘bad’ looks like. Unfortunately I wasn’t in control of that either – I just coloured the numbers.

By the time the numbers reached the inspectors, the criteria for ‘good’ colours had managed to exceed the criteria for ‘good’ numbers. This meant that the colours looked a lot better than the numbers. But the inspectors didn’t have the colours. And with the criteria that we had given the inspectors the numbers did not look good. And when the numbers don’t look good, it’s easy to go and look in books and find evidence that proves that the numbers were never so good in the first place.

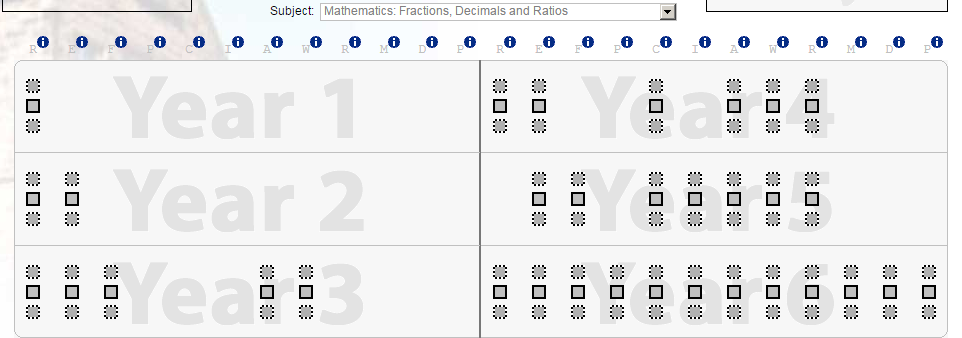

With the new assessment without levels and every school building up their own system from scratch, it’s vital that school leaders don’t lose the big picture of what their assessment system actually shows. If you say to inspectors “our children are making better than expected progress, and look, our assessment system shows it,” the inspectors will simply pick up some Year 2 books and some Year 4 books and see if there is evidence to show the ‘better than expected progress’.

If that evidence doesn’t exist, it doesn’t matter how much you have coloured the numbers, the assessment system is broken.